Four years ago, Sudanese revolutionaries overthrew long-time dictator Omar al Bashir through persistent civil resistance after military and paramilitary units sided with the protesters. Since 15 April, two leading generals and protegees of the old regime are fighting each other bitterly - once again at the expense of the civilian population. But the power of resistance has not been broken: Sudanese are in the process of forging an anti-war alliance.

"We had no electricity. That's why I'm only writing now. Yesterday they found my brother-in-law dead in the street. Shooting, all night long, now also fighter planes and helicopters. So many dead on the streets - pray for us".

This is just one of the many horrifying messages friends have been sending from Sudan since the early morning of 15 April. “Once again”, long-time observers of the political situation in this important country at the Horn of Africa may be tempted to say. However, one can and should never get used to terror, death and displacement. The people who are exposed to this always deserve our full attention. Even if events seem so predictable. Even and especially when, as in Sudan and elsewhere, they are repeatedly caused by the lust for power and the greed for money of individual men.

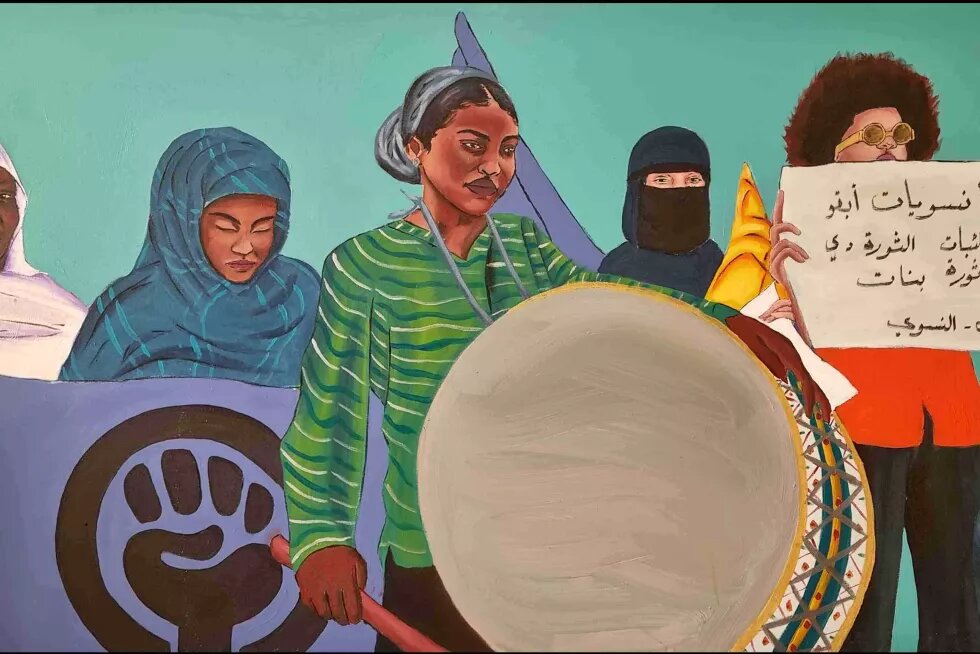

Almost exactly four years ago, the people of Khartoum - and many around the world - rejoiced in the streets. Through persistent civil resistance and peaceful protests throughout, the revolutionaries, who were clearly made up of young people and women especially, succeeded in overthrowing the long-time dictator Omar al Bashir, thus putting an end to the much hated, corrupt Islamist government. The pictures went around the world. Sudan became the symbol of what peaceful resistance can achieve. Many outside the country, however, quickly forgot the high price they had to pay. The fact that the military and its paramilitary units sided with the protesters was ultimately decisive for the fall of the regime. The two leading figures were Abdelfatah Burhan, General of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and Mohammed Hamdan Daglo, called Hemiti, leader of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). They thus opposed not only their commander-in-chief but also their own "foster father" with whom they shared their political affiliation and Islamist background.

It is these two who have been fighting so bitterly against each other since 15 April - once again at the expense of the civilian population. Both had already shown that they have little regard for the civilian life: Hemiti as leader of the Janjaweed, the notorious militia of horsemen in Darfur, responsible for mass killings and expulsions there at the behest of the government; Burhan, among other things, as commander of the regional wars in Darfur and South Kordofan. They both became rich in the process.

Trust in military leadership damaged push for democracy

So it seems almost logical that in 2019 they tried to claim power for themselves and prevent a democratic transformation of Sudan. Their attempt to forcefully push back the revolutionaries culminated in a massacre of at least 150 civilians in Khartoum in June 2019, for which no one has been held accountable to date. The protesters, however, were not deterred and continued regardless. Supported now by pressure from the international community, they finally succeeded in getting a joint transitional government of civilian and military forces formed. The transitional council was headed by General Burhan, his deputy became Hemiti, and the civilian leadership was entrusted to the new Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok.

Hemiti succeeded in negotiating a peace agreement with most of the remaining armed rebel groups, whose leaders were given important positions in the Transitional Council and in the government. However, this greatly strengthened the military element in the already fragile government.

Relevant voices from Sudanese civil society had repeatedly pointed out that it was far too risky for a real transformation to a democratic society to trust the military leaders, who, moreover, were predominantly Islamist. This warning proved all too justified in October 2021. When, according to the original agreements, power in the transitional council was to rotate to the civilian forces, the military forcibly removed the prime minister and suspended important parts of the agreements - a coup.

Up to this point, Burhan and Hemiti had marched in "lockstep". Subsequently, too, common interests, including increasing their wealth through gold mines, companies and real estate, but also providing mercenaries in Yemen and Libya, led them to reject civilian elements in the government. Members of the Bashir regime arrested in 2019 were released, frozen accounts reactivated, Islamists brought back into the apparatus. Regional as well as international alliances, however, were pursued rather separately. The Russian Wagner troops, for example, had long been active alongside Hemiti in the country. Russia and Eritrea remained important allies for him. Egypt, among others, supported Burhan to prevent democratic change.

The Sudanese, however, did not give up their resistance even in the face of the steadily deteriorating economic situation. Sudan, at 40%, had the highest inflation in Africa in 2022. Now more than ever, many are deeply convinced that any tyranny in Sudan must be brought to an end once and for all. However, there has been no consensus on how to get there. Thus, parts of the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) remained in negotiations with the military in a process facilitated by the UN Special Representative for Sudan and accompanied by many other foreign envoys to form a new government - precisely those classic negotiations with the tyrants that the "street" rejects outright. In November 2022, a new provisional framework agreement was finally agreed upon, which, supplemented by important addenda, should have been signed shortly before Christmas and then implemented.

But this was not to happen. Rejected by many revolutionaries anyway, two points in particular contributed greatly to the long feared open power struggle between Hemiti and Burhan: the integration of the RSF into the regular armed forces and the question of accountability for the massacres. Verbal attacks on each other increased, but both continued to claim that they were not interested in an escalation. But this is exactly what has happened since 15 April, a power struggle between two men who both claim to have acted in the interest of democracy.

Sudan’s democrats forging an anti-war alliance

Hemiti had already increasingly tried to establish himself as a civilian leader in recent months and even went so far as to distance himself from the coup in October 2021. The true democrats and all peace-loving Sudanese, however, vehemently reject his window dressing. They are in the process of forging an anti-war alliance - and for many, despite all the new suffering, the power of resistance has not been broken. Whether they will once again succeed in initiating a new, democratic path with reunited forces seems at least uncertain at present, in view of the military threats. The danger of a resurgent Islamism or of Sudan drifting apart along ethnic lines has not been averted, nor have the dangerous spill-over effects in the fragile region.

How neighbours, allies and the international community in general behave will be crucial. So far, they are at least verbally united in their rejection of military escalation. However, it remains to be seen to what extent everyone is really prepared to consistently demand the democratic change that the Sudanese people are longing for and to support it just as consistently.

Marina Peter is head of the Sudan and South Sudan Forum and has been working with Sudanese civil society for peace, reconciliation and democracy for more than 30 years.