As Lagos pushes to become a 'world-class' city, gentrification increases with more low-income residents being displaced under the pretext of 'public interest'. This research summary explores how evicted victims are impacted and its implications on trade and the Lagos economy.

In the past twenty years, Lagos State authorities have forcibly evicted over 2 million Lagosians from their homes and workplaces, according to a 2017 Amnesty International report. In Nigeria, the government has the power to acquire and revoke any right of occupancy, as contained in the Land Use Decree and the (Federal) Compulsory Land Acquisition Law Cap 167, as long as the land is being revoked for a public interest project. The broad discretion of government authorities to interpret ‘public interest’ has remained unchallenged so far.

Looking at the Badia-East community, Babs Animashaun mechanic village, the Oyingbo and Tejuosho Ultra-Modern Market complexes, the Eric Moore and Moloney towers, it needs to be asked: what kind of value does the reuse of eviction sites bring to the Lagos society and economy? To what extent do such evictions really contribute to the city’s economy and social landscape in service of ‘public interest’?

The economic impact of evictions in Lagos State is closely connected to the state’s relations with, and increased reliance on, private capital. In today’s globalized world, large infrastructure projects have emerged as a popular strategy for cities to attract private capital and to reposition themselves as ‘world-class’. Since colonial history, Lagos has seen several planning interventions to manage its urban growth strategy, including an ambitious UN-sponsored ‘Master Plan for Metropolitan Lagos 1980-2000’, which fell short due to lack of personnel and equipment and inability to cope with the phenomenal population growth. In 2005, a partnership between the Federal Government and the Lagos State government resulted in the launch of the Lagos Megacity Project (LMCP) to revitalise the Lagos State’s urban strategy and to reinvent Lagos as a modern megacity. The project gained momentum under Babatunde Fashola’s administration (2007 – 2015). During Fashola’s administration, the Lagos State Development Plan 2012-2025 was introduced to accelerate the state’s infrastructural development schemes in order to attract global franchises to contribute to its economy.

In executing its development plans, the Lagos government has increasingly relied on private investors given its history of difficulties in mobilising public funds through federal or state alliances due to opposition politics and a highly politicized federal resource allocation system. Public-private partnerships and international development projects continue to be regarded as serving the general Lagos public simply because they promise to inject the state’s economy with revenue and create job opportunities. It is assumed that slum dwellers and informal street traders cannot and do not bring in the same revenue as expensive residential estates and malls. Many of these projects end up necessitating evictions to deliver Lagos from its slums, squatters, and dead capital, which are all taken as markers of disorder and inefficient use of resources.

On the surface level, the story ends here. However, looking more closely, for example, at the five aforementioned eviction sites, shows that when this aggregate benefit is deconstructed, evictions amplify already existing inequalities, often re-create old problems, and are not always the only or best solution.

The re-usage of eviction sites can be seen as economically efficient only if efficiency is understood as solely revenue increase. Let us consider a fairly successful case study: the Tejuosho Ultra-Modern Market in Yaba. Following fire damages in 2004 and 2007, the old Tejuosho market was reconstructed in 2014 in two phases, each one a four-storey building. The two phases were developed and financed by different sets of private development companies, banks and investors. Different private real estate management companies now run the two buildings and they both have a near-total occupancy rate. Traders who were interviewed reported a four-times increase in revenue. This is good news until we consider that increased revenue does not necessarily mean increased satisfaction and ease of doing business for the traders. After reconstruction, shop rents rose to triple their previous cost and along with increased maintenance fees, they now eat up most of the traders’ increased revenue. Additionally, traders complained of a lack of transparency in the operation and maintenance fees they have to pay. Those trading in the lower-rent stalls complained about frustrated access to customers, poor management, and electricity supply but were not able to move to other parts of the market because they could not afford it.

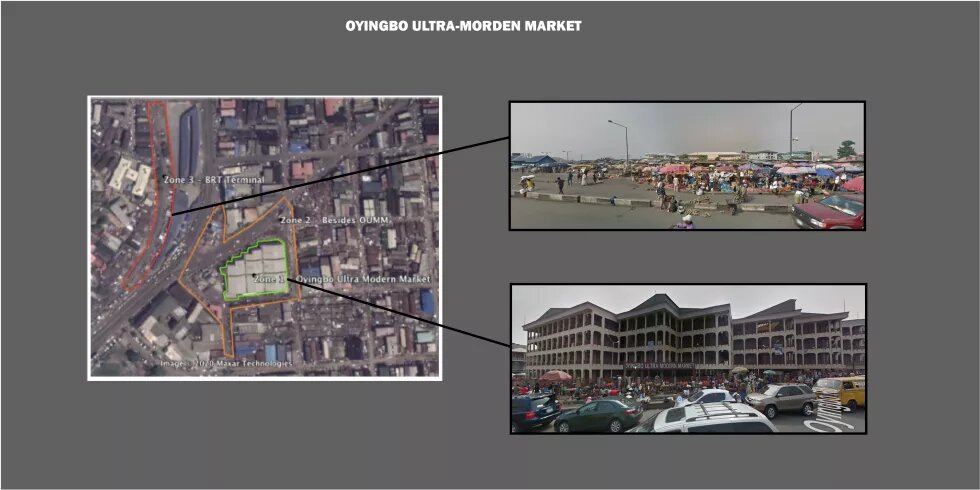

A less successful story is the Oyingbo Ultra-Modern Market in Ebute-Metta. This market was demolished in 1991 to be reconstructed into a complex, which was finally completed in 2015. In the twenty-four years between demolition and reconstruction, traders innovated around the space to continue their businesses on the roadside and nearby streets. In 2015, Oyingbo traders faced yet another upheaval as most of them were displaced again to make way for the four-storey building complex that stands as the new and ‘ultra-modern market. Deaths and lasting injuries have been reported following the violent demolitions and evictions. One trader at Oyingbo described how the demolition task force attacked them with dogs and horses. Traders also lost substantial percentages of their income in the adjustment and sell less now than they did before the 2015 evictions. One of the traders described how she had to borrow N300,000 to rent one of the spaces in the new complex only to end up sitting in her shop all day and seeing no customers. She also complained that the design of the complex made it nearly impossible to solicit customers in the way her trade demanded. “I’m thankful to whoever built it,” she said with sarcasm, gesturing to the complex behind her, “but me, I’ve just decided to stay in a place that profits me. They want me to move up there and be shouting for customers? At my age, how will I start carrying all my things up the stairs every day?”

Like her, most other traders do not find the new Oyingbo complex profitable. Unlike Tejuosho, Oyingbo is managed by the local government and does not enjoy the economies of scale Tejuosho enjoys by virtue of its location. The new building’s poor design and high rents have meant that most traders continue to trade outside on the street or in the 150-car capacity parking space in the basement. As of September 2020, five years after the complex was completed, only 52% of the shops are occupied. At the end of the day, the estimated one billion naira that was put into Oyingbo would have been of greater value if the traders themselves were included in the design process. While there is increased transport efficiency around the area because of reduced traffic, the project continues to stand as an example of low economic and low space efficiency.

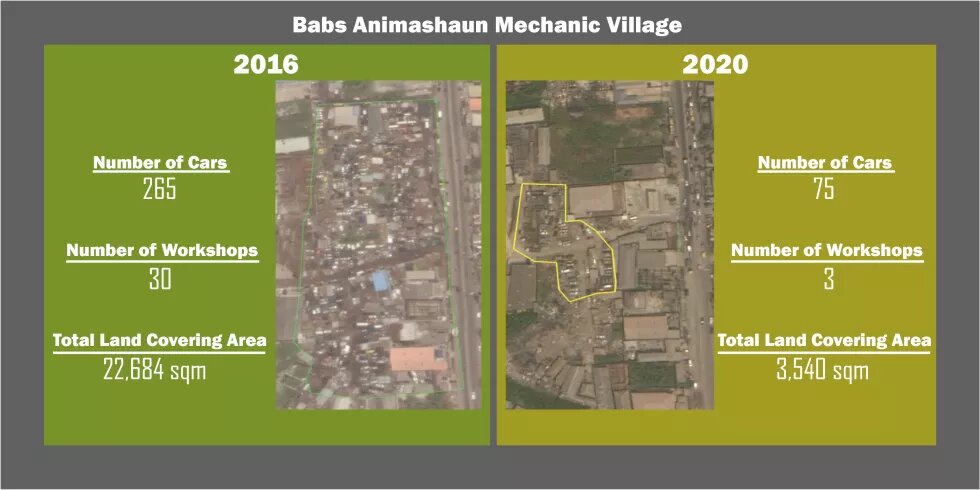

The current re-use of the Babs Animashaun (B.A.) Mechanic village site also reveals limits to the economic benefit of evictions. Located in Surulere, the B.A. The mechanic village was created in 1980 to ease Lagos roads of mechanic activities that congested traffic. According to the workers, there have been three evictions: in 2007, 2014, and 2016. The most recent eviction was carried out through demolitions that shrank the total land-covering for the mechanic village activities from 22,684sqm to 3,540sqm. Rationales for the evictions ranged from security concerns to beautification purposes and the risk of doing mechanic work under the high-tension electricity grids in the area. The government gave the land to the mechanics in 1980 under the promise that the technicians will not be relocated unless for national development. Yet, as of September 2020, the land had been sold by the Lagos State Government to private owners who have re-appropriated the land for a petrol station, four churches, and other uses that do not match the rationale given for the evictions. The new petrol station was built under the electric power line and now constitutes an even more dangerous hazard. A visit to the mechanic village today raises doubt over the fulfillment of the beautification rationale for the evictions.

The demolition of the B.A. mechanic village came at the expense of thousands of technicians who had worked in the village for an average of 31 years among them. Majority of the technicians lost at least two-thirds of their income from the evictions and none of them was promised compensation. This has a significantly larger impact on the general Lagos society when we consider that these technicians are aged between 40 and 60, and have families who depend on them. They were not transferred to another site. To date, the mechanics are still campaigning for a resettlement action plan from the government. No doubt, the demand for car repairs remains, therefore evictions, such as these, will only increase the pressures on other mechanic villages in Lagos and transfer traffic and environmental issues back to other Lagos roads, thereby increasing traffic congestion and thus recreating the problem solved in 1980 when they purposely assigned the space to the mechanics.

In the cases of the markets and mechanic village, not only do the evictions cost the evictees a significant proportion of their means of livelihood, but they have also failed to reach their potential as economic development schemes done in the public interest. The evictions resulted in an increased level of precarity among workers and job losses affecting several dependants and Lagos’s economy at large. While the intention of ‘public interest’ and ‘development’ are often well-meaning, in practice, they have been executed with poor design and violent implementation that has undermined their impact.

The social impact of evictions and the re-usage of eviction sites is best evaluated when broken down into security, environmental factors, and urban inclusion.

The Lagos State government often cites criminal activities and disorderly behaviour as part of the problems evictions solve. Often, slums and informal settlements are accused of constituting environmental hazards and providing cover for criminals.

For claims of criminality as a rationale for home evictions, let us look at the Badia-East settlement in Apapa local government area. Badia-East is an informal settlement whose total land-covering has shrunken from 150,000 sqm to 6,572 sqm in the last ten years alone. Since 1920 when the government claimed the land to build a railway line, Badia-East has been a site of contested possession. In 1973, the community was evicted and resettled in a nearby area by the Federal Government to make room for the National Theatre. Between then and now, the community of about 100,000 inhabitants has faced four forceful evictions in 2012, 2013 and 2015, and 2017.

In an interview with Mr Adesoji*, a community leader at the Badia East community, he admitted that some of the people currently occupying the area were only there because they sell hard drugs and operate other illicit businesses. But another community member, Mr Onimode*, insisted that claims of the community enabling criminal activities are a simplistic and malicious accusation which the government uses as a rationale because, while they accuse the community residents of being criminals, they cannot point out an actual criminal activity. “Even the government officials that are calling people here criminals are embezzling funds, is that not criminal? Can a normal person embezzle?” In other words, slums are not the only, or the most notorious, sites of conflict and criminal activities.

Evictions, in and of themselves, do not enhance security levels in Lagos. Instead, they escalate the threat of insecurity faced by Lagosians. Evictees of both workplace and homesites are left more vulnerable to harassment and violence. Not only are evictions in Lagos notorious for being brutal processes, but they are also often done without proper resettlement plans as both the Badia-East and Babs Animashaun case studies show. The financial, health, and social burdens caused by the upheaval of evictions done without due process of resettlement and compensation leave evictees with fewer resources to protect themselves from their increased vulnerabilities. Furthermore, re-usage of the eviction sites for private estates and evictions that do not look out for the evicted communities could increase the general crime rates in Lagos.

A major pillar in the ‘public interest’ rationale the Lagos State government uses to justify evictions is the combined factor of environmental and sanitation concerns. Since Fashola’s administration, urban planning in Lagos has enhanced the physical appearance of the state, decongested traffic in many areas, and increased sanitation levels. Evictions have played a part in this. For example, the renovation of the Oyingbo market site, particularly its BRT terminal area, has had significant transport benefits.

On the flip side, evictees from informal settlements and low-income communities such as Badia-East suffer worse sanitation levels after evictions. Three years after the last forced eviction, two-thirds of the remaining Badia-East community members stressed that their environment has gotten dirtier with large amounts of waste accumulating around them with little or no penetration of the state’s sanitation services in their area, and for most, their previously bad access to water had gotten even worse. There are only two plastic water tanks accessible to the community but even the water there is too expensive for them. Instead, they go all the way to the Nigerian Breweries site, located 2.5km away, to fetch their water. While this may seem like an insular disadvantage suffered only by evictees, one only has to consider that environmental pollution draws no boundaries. In the case of Badia-East, people were even evicted to make space for a canal built in 2012 as part of the World Bank upgrading project to mitigate the impact of flooding, and today it has accumulated solid waste inside and alongside in heaps.

One under-considered implication of evictions and the re-usage of eviction sites is the ways they enact a politics of belonging to the city. Every eviction sets a precedent for what values are prioritised above others and who belongs in a particular space. In 2005, a series of home evictions were carried out across Lagos in effect to the Federal Government 1991 decision to privatize public residential buildings occupied by civil servants, which affected about 20,000 people. The main reason given by the Federal Government was that private investors would have the financial capacity to maintain the decaying infrastructures. Some of the buildings affected included the Eric Moore and Moloney towers, which accommodated top-level civil servants. These buildings were eventually sold to private oil and shipping companies respectively. Yes, the private owners have been able to maintain the buildings over the years, but the maintenance has come with high rent prices that aggressively push inhabitants out of their homes. As part of the process of gentrification sweeping across Lagos, home evictions such as these raise the question of whether Lagos city today is repositioning itself to cater to the interests of capital over the interests of its people.

The pattern emerging from the evictions shows that the Lagos State government abuses its power in its current land laws. The State Land Law, Laws of Lagos State 2004 Vol. 7.S.II provides that 'Public Purpose’ includes any purpose deemed to be for exclusive government use and so permits the government to make eviction decisions without consulting the public or affected communities. However, it is the needs of private investors that are mostly considered. Take the Jubilee Estate currently being built around what is left of the Badia-East settlement: in 2015, the real-estate development and management company Brains and Hammers began “The Jubilee Estate” project following the fourth eviction faced by the community. The project was celebrated as a plan to drive urban re-development in the area and convert the area to a highly sought-after residential area. It was pitched to create 400 direct jobs and about 3,000 indirect jobs in the area currently occupied by informal artisans, labourers, traders, and food vendors.

Most of the community members forcibly evicted did not receive a notice and some are still not aware of the reason they were evicted in 2015. The 2015 evictions made way for a 2-phase development process of the project; the first phase is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2021. However, in 2020 the project was expanded to include a third phase scheduled to commence this year on part of the land members of the Badia-East community currently live. When asked if those community members are aware of their imminent eviction, a representative of Brains and Hammer flippantly replied: “No, it is not an urgent matter, but we will engage the community when the time comes.”

The ‘ultra-modern’ continues to be prioritised by the Lagos State government and its city planners. And belonging to Lagos, as in many cities around the world, has increasingly become a question of income levels. Currently, low and lowest-income earners are mostly affected but the evictions of residents in the Eric Moore and Moloney towers show that people of higher income brackets are also at risk of displacement.

All of this begs the question: How can development be brought to the city without recurring dehumanising evictions? Across the case studies looked at, due processes of notice, compensation, and relocation according to the UN’s ‘Basic Principles and Guidelines on Development-based Evictions and Displacement’ have not been adequately followed. These evictions directly harm and impoverish the lives of the evictees and they also have negative consequences for the development of the Lagos State economy and society. It is not inevitable for social and economic development to come at a cost so high. Changes can be made through advocacy, policy, and the law.

In cases of forced evictions, civil societies have tended to focus on advocating for a change of the Federal Land Law, which is included in the constitution and so takes a much longer and complicated process to amend. It is more likely to get the 2004 Lagos State Land Law modified to ensure a more democratic decision-making process to urban planning in the city. In reviewing the law, a dedicated section for stakeholders’ engagement will be necessary. If the law mandates the state actors to engage and consult with the residents on the decision to declare a land for public purpose, there will be less violent approaches to recover and re-appropriate land use.

It is also necessary to improve the level of transparency and inclusion of civic participation in the design and decision-making process for rebuilding public utility properties such as markets. Not only would this result in greater user satisfaction, but it is also more likely that people would use the facilities in a way that does not lay renovation efforts to waste. Instead of backfiring against its intention, a user-participatory design will lead to increased economic efficiency.

Additionally, it is worth considering the ways eviction patterns relate to the more widespread phenomenon of gentrification in the city. Even the in-situ slum upgrading schemes can lead to gentrification as we can see in the market case studies where traders struggle to pay the new rent for spaces in the ultra-modern market complexes and so are pushed away from trading in the area. Trends in the re-usage of eviction sites show a binary approach towards housing, belonging, and ownership in its urban planning. The Lagos State government should use mixed-income housing policies to address this issue. This would entail incentivising developers to offer a percentage of residential projects as “Below Market Rate” to be rented at a cost that is affordable to lower-income households either on-site (within the project) or at another location in the city.

The pressure to be a ‘world-class city’ is pushing Lagos to prioritise capital over people’s welfare. It is time for the Lagos State government to recognise that evictions and the re-usage of eviction sites tend to serve the interest of a few and not the wider public.

Watch the full feature film on Dispossess below

DISPOSSESS - Evictions for Development? (FEATURE FILM) - Heinrich Böll Stiftung Abuja Office

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube

*Names have been changed to protect the individuals’ identities.

This article is a summary of the research of five eviction sites commissioned by the Heinrich Boell Foundation Abuja office. Facts and statements from evictees are drawn from this research. Please click here to download the full report.

This article first appeared here: ng.boell.org