A tragedy befell the inhabitants of the Senegalese city of Thiès in January 2022. This article is about the demolition of their homes, forced displacement and the brutal nature of development-induced displacement.

Introduction

In Africa, as is the case elsewhere across the Global South, the phenomenon of urbanization poses many challenges. Chief among them is the question of land governance, on which the very foundation of urban life is built. Peri-urban areas, with their composite land tenure systems and dynamic land markets, can be severely affected by urban expansion. Their integration through the building of roads and transport systems is a matter of growing concern for policymakers.

The integration of poorly connected peri-urban neighbourhoods into cities through the development of mobility infrastructures or public facilities often results in tussles over land and property. Not infrequently, disputes can escalate into volatile situations that end in the displacement of populations that are unable to protect their property rights on land they have settled; nor are they in a position to insist on compensation for losses incurred as a result of their displacement by development projects. Because of their precarious situation vis-à-vis land, these populations are often among the first victims of urbanization.

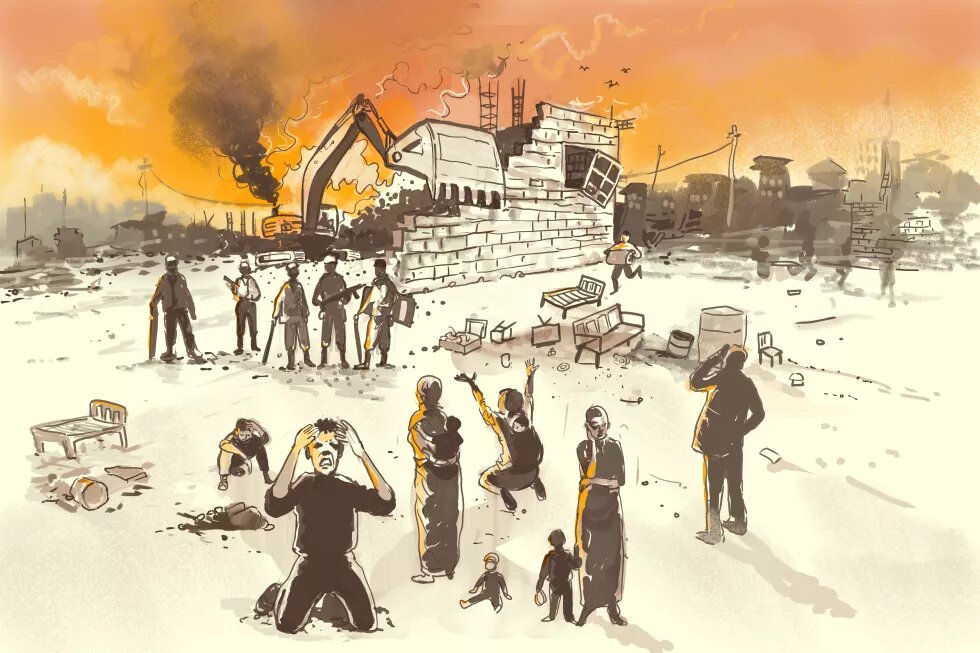

A tragedy that befell inhabitants of the Senegalese city of Thiès in January 2022 illustrates this perfectly. Some 2,000 inhabitants of the Mbour 4 neighbourhood on the outskirts of the city of Thiès in western Senegal were displaced when their homes were destroyed on the sole pretext that these structures were built on an area classified as a Senegalese state domain. This article is about the demolition of their homes and forced displacement, as captured by the adjacent video, which reveals in shocking detail the brutal nature of development-induced displacement.

Background

Thiès is the second largest city in Senegal, both in terms of population and economic importance. Around 70 km from Dakar, it is a dynamic urban centre experiencing strong population growth, mainly due to immigration. This inward movement of people owes to its proximity to the capital, its economic role, and also its comparatively low cost of living when compared with Dakar.

Migration and settlement to Thiès has taken place on state-owned land. For more than 20 years, the authorities have permitted this and even provided the resident population with services, connecting them to the city through various economic processes and networks without awarding property titles. Against this backdrop, on January 21st and 22nd 2022, the authorities of the Direction de la Surveillance et du Contrôle de l'Occupation des Sols [DSCOS] forcibly displaced more than 2,000 people by simply destroying their homes. The misfortune of this population was to have settled on a strip of land in the city’s last remaining land reserve - a gazetted forest - at a time when major infrastructure projects were being announced.

Demolitions took place in the context of a project to improve urban mobility by connecting the city of Thiès to a new motorway. They occurred, according to the affected population, without warning. Protest and political tension resulted as an entire population was commanded to leave the area without any support or options for organized resettlement.

Building this house was the fight of my life… Today all my efforts are in vain

In the middle of his ruined house, Moustapha Ndiaye sorts through the rubble in the hope of finding useful objects. However, the bulldozers have razed everything to the ground and all he can do is look at the damage: ‘Building this house was the fight of my life. I invested all my savings in it so that one day I could leave the family home, which had become too small to accommodate my family. Today all my efforts are in vain.’

With loudspeakers, policemen order the fathers of the families to leave the houses in order to demolish them. Another disbelieving victim watches the destruction of his house with bitterness: ‘The land they will take from us here, they will give it to others. And yet we are Senegalese and have the right to have land to build our houses’.

Families withdraw into prayer to implore the Lord to help them. Women and children shed hot tears, perhaps contemplating the cool night air they will be at the mercy of since they are now homelessness. Images of some of them sobbing did the rounds on social media.

The images are appalling, words fail to describe the destruction.

Explaining Displacement at the Peri-Urban Frontier

It is difficult to understand the sense of urgency that appears to have compelled the authorities to destroy these homes in such a hurry. Some context may be helpful.

In Senegal, the right of access to land is recognised in law, most notably in the right to property granted by Article 8 of the Constitution. A plot of land for residential use is obtained by purchase or by letter of allocation in a housing estate monitored and implemented by the state's technical services.

In Thiès, the problem started with a 92-hectare subdivision, 67 hectares of which encroached on the classified forest of Thiès. In fact, in 2006, the commune initiated a subdivision which had respected all the procedures, and a subdivision permit was issued. But after some time, with the complicity of certain state services, several constructions were erected without building permits.

Over the years, notorious irregularities have accumulated, raising several questions. How is it possible that state-sanctioned services (mainly water and electricity) were available in an ‘illegal’ occupation zone, allowing the inhabitants to live there? Were guarantees given to the occupants at a time when their settlement was perceived as convenient? Was connecting Thiès to the new motorway the sole imperative behind the push to displace settled populations? Or was the extension of the road a pretext for demolishing the buildings?

Moreover: It is well known that financial compensation could and should be paid in the framework of displacement policies. A special commission, often headed by the authorities, should be set up to make the necessary compensations. In the specific case of Thiès, those who witnessed the traumatic destruction of their homes have not yet received any kind of support or compensation.

Conclusion

This situation in Thiès raises serious questions about land governance in African cities, where land governance is characterized by illicit enrichment of various actors in an environment marked by endemic corruption. Thanks to the graft of elites, inadequacy of urban planning, and failures of land management policies, it is not an not isolated case.

If the state feels aggrieved at extra-legal processes of informal settlement and wants to address them, it should sanction the members of the land commission and not the purchasers of plots who have invested lifetimes neighbourhoods such as Mbour 4. These demolitions were carried out in a way that flouted the basic rights and dignity of the populations concerned; no court decision authorized the demolitions. The Direction de la Surveillance et du Contrôle de l'Occupation des Sols (DSCOS) is a branch of the police responsible for monitoring state or national land titles. It does not have the power to destroy homes belonging to individuals. It should be the court that condemns and authorizes the destruction or not of buildings. In a state governed by the rule of law, only court decisions can sanction the destruction of property belonging to others.

In Thiès, the state should compensate the owners of plots of land since it was a state commission that officially allocated the plots. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon to see citizens’ basic rights ignored when it comes to dealing with the all-powerful government machinery of States in the Global South.

-----

This article is part of the Dossier Urban Displacement. Forced Evictions: Stories from the Frontline in African Cities