Forced evictions are a form of invisible displacement. Their causes and consequences for communities can be devastating; the benefits they bring are unclear. Why then, do they elicit such little concern among policymakers? This richly illustrated multi-media dossier contains reportage, analysis, policy recommendations from several African cities as well as oral testimonies on migration and displacement in Nairobi.

Are forced evictions a form of displacement?

In the policy sphere, populations uprooted by real estate and infrastructure development in cities rarely attract the attention of governments, humanitarian and migration agencies. In their operational work and data collection, the latter tend to focus on refugees, border-crossing migrants, and internally displaced persons (IDPs) driven from their homes by ‘natural’ disasters and conflicts.

Among think tanks and foundations, there is growing interest in urban migration governance reflected in excellent initiatives by the Bosch and Samuel Hall foundations. Here too, however, the problem of forced evictions rarely elicits sustained focus.

As for academic research, little seems to have changed since 1990 when the American sociologist Michael Cernea wrote: ‘An unjustified dichotomy in the social sciences literature dealing with displaced populations separates the study of refugees from the study of populations uprooted by development projects.’

In research, as in policy, the assumption seems to be that displacement results from political or environmental change rather than economic development: Entire communities may be dispossessed of land and/or property and forcibly evicted from dwellings multiple times over their lifetimes without being classified as displaced persons.

In short: If forced evictions are a form of displacement, they are largely invisible.

The reasons for this are political. The expulsion of populations from their dwellings to make way for infrastructure or the construction of property often results from policy decisions and/or actions taken by government authorities in alliance with private interests. Such powerful actors are well-positioned to shape media coverage, policy agendas, and broader narratives about what kinds of issues warrant public debate. In contrast, populations that bear the brunt of development-induced displacement tend to be politically voiceles; they lack the kinds of resources required to influence decision-makers and journalists.

Apart from a handful of dedicated local and international civil society organizations and collectives such as the Housing and Land Rights Network/Habitat International Coalition, nobody much cares to map the numbers of people affected by land and property rights violations. As for the misery inflicted by forced evictions, this too is neglected by all except a handful of organizations and individual bodies within the UN system that have commissioned reports and briefs that demonstrate beyond doubt what should be obvious: forced evictions are an unnecessary evil; one that is preventable, and whose consequences must be addressed under the growing gamut of initiatives directed towards alleviating the impacts of protracted displacement crises.

Forced evictions are by no means a uniquely African phenomenon. In the 1950s, New York City authorities famously drove hundreds of thousands of predominantly poor and disproportionately non-white New Yorkers from their homes under a ‘slum clearance’ program led by the urban planner Robert Moses. Today, across the Global South, similarly callous approaches to modernization built on middle-class aspiration at any cost are now dominant.

African cities have become fertile ground for the kinds of elitist ‘plug-in’ infrastructure projects associated with this mode of urbanism. The latter are often imported and financed externally by development and lending agencies, and of course China. (The Nairobi Expressway is a case in point).

Furthermore, they are implemented in contexts where land governance is subject to manipulation by private interests. In combination, these different factors combine to produce predatory urban environments in which forced evictions are routine.

The research, analysis, and story-telling collated in this dossier show that in their consequences, forced evictions can be devastating. Thriving areas of human settlement are left looking like war zones. Not just dwellings but livelihoods are destroyed; access to services like schools is disrupted; belongings are lost by those who can least afford to lose them; physical harm and psychological trauma is experienced, both directly in violent encounters with police forces, and indirectly, for instance, by women forced into destitution which can result in other forms of abuse.

It is ironic that so much of this suffering takes place in the name of improving mobility and inter-connectivity between people and markets. Several of the cases explored in this dossier focus on the building of airport roads, high-level bus services, and other transport infrastructure that purports to integrate populations and zones of commercial activity.

Connectivity and economic integration for some, it seems, means severance of others from their homes and livelihoods, and disintegration of their communities. Often it is the poorest who must endure, but, as evidence from Senegal suggests, Africa’s emergent middle-classes are not immune from the dysfunctions of ‘plug-in’ urbanism. This is clear in peri-urbanareas/secondary cities such as Thiès, and even metropolitan cities such as Nairobi, as Constant Cap points out in a forthcoming podcast.

At present, the dossier features articles by partners of the Boell foundation’s Dakar office, which is currently exploring modes of sustainable development and public participation that can ensure social and ecological justice for all citizens. It also includes writings originally commissioned and edited by colleagues in Abuja, who have been monitoring urban development in Lagos for close to a decade… The story there, captured evocatively in documentary format and fact sheets by organizations resisting the dominant agenda is not dissimilar to the picture in Nairobi, where the resilience of mobile individuals and communities is being tested to the full. Among the many messages that emerge from testimonies gathered by Irene Asuwa, is that forced evictions in Nairobi intersect with many other types of movement, voluntary and forced, in the lives of men and women who witness or undergo them. Moreover, they are experienced as one among many other challenges and forms of violence that form the fabric of everyday life in informal settlements.

What is to be done?

Policy recommendations are best formulated differently for diverse national contexts, whilst taking into account regional, continental, and international frameworks of law, not least the Kampala Convention. This dossier features a recent review of the IDP situation in Ethiopia, which is dominated by conflict but touches on development-induced displacement. Kenyan law and decision-makers will also be offered recommendations in the form of a policy brief following consultation with civil society and stakeholders on August 28th 2023. There will also be a role for supra-national bodies like the UN, humanitarian and migration agencies.

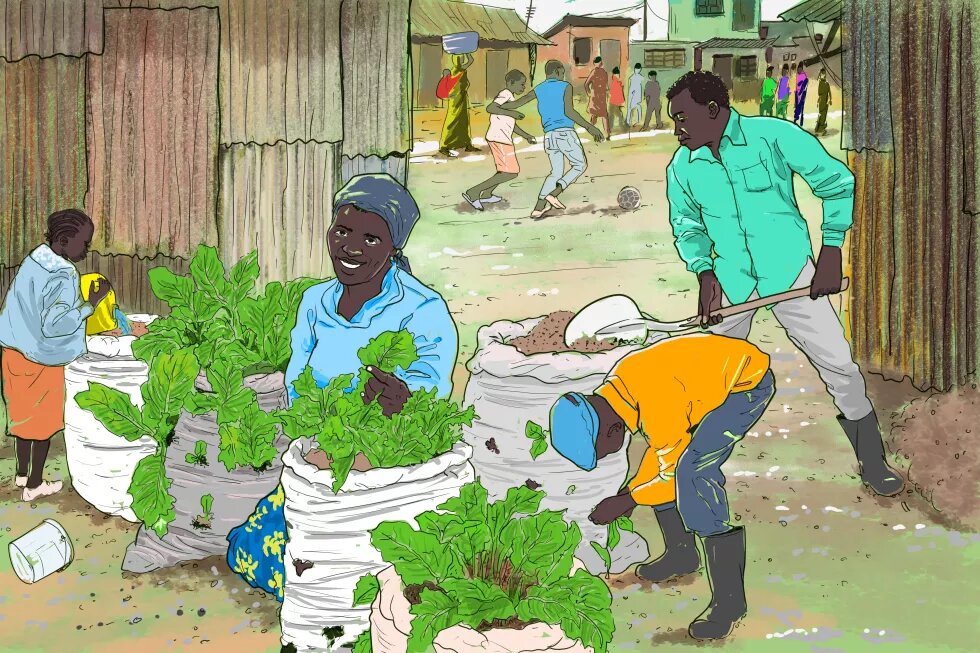

In the context of struggles for climate justice and the current cost of living crisis, it is worth noting as a concluding aside that many of the Nairobians interviewed by Asuwa expressed keen interest in agro-ecology, a cause long championed by the Boell foundation’s Kenya office. Aside from its obvious material importance, the metaphorical quality of this call for seeds - for growers to be supported to establish and strengthen roots - should not be lost among those whose responsibility it is to govern cities inclusively.

-----

This editorial is part of the Dossier Urban Displacement. Forced Evictions: Stories from the Frontline in African Cities